In August, 2019 TUNDI Productions – an opera company founded by soprano Jenna Rae and conductor Hugh Keelan – staged its inaugural Wagner in Vermont Festival with a pair of astonishing performances of Tristan und Isolde at the Latchis Theatre in Brattleboro. After the pandemic imposed three long years of stage silence on them they returned in August, 2022 with performances of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre. While not exactly the clap of thunder in a blue sky that their Tristan had been – really, how could they have been? – they certainly confirmed that that Tristan had been no mere happy accident. And now, this past August, 2023, they have mounted their third Festival – Walküre again (though in essentially a new production) and Siegfried – and it is clear, if it hadn’t been abundantly clear before, that something extraordinary is happening in the Green Mountains, on the banks of the Connecticut River.

What’s special about TUNDI? That invites a more fundamental question: What’s special about Wagner? I believe Nietzsche was entirely correct when he wrote, even as he was breaking with his former friend, “...Some things have been added to the realm of art by him alone, things that had hitherto seemed inexpressible and even unworthy of art…some very minute and microscopic aspects of the soul…indeed, he is the master of the very minute.” As stirring and moving as Wagner’s music can be simply as music – and I consider it axiomatic that his music is some of the best ever devised in the Western tradition – his art finds its true depth in in the depths of the soul, or what today we would call “psychology,” and when we plunge into it we plunge into vast seas of ineffable human emotions and primal human drives. He created characters as fully rounded and rich in feelings as any to be found on stage or in literature – and more rounded and richer than most. And while they’re often larger than life they're never grotesque or misshapen giants (not even actual Riesen). His chosen form was drama, the most human of the arts – human beings are its raw material, after all – and he was a dramatist first, last, and always, albeit one for whom music (and not words) was the primary means of expression. Again, Nietzsche was correct: “he was essentially…a man of the theater and an actor…” Though to him that was condemnation and not praise: “What is the theater to me?...What, the whole gesture hocus-pocus of the actor!” To him it was nothing, or even less than nothing – contemptible. But for those of us who love Wagner, theatre should be something like the whole world. It certainly seems to be for the artists of TUNDI, who have notably used their thespian magic, their actorly “hocus-pocus,” to create a deeply psychological theatre, a theatre of living souls.

Tristan is probably the supreme example of a thoroughly interior and psychological drama; it’s not really “about” its minimal plot, but rather what it feels like in the eternal now to be obsessively in love and lust. It was the perfect choice for TUNDI to offer as its initial production. (Indeed, the company’s name is derived from Tristan UND Isolde.) The Ring is certainly quite different, being much more plot driven and concerned with the externalities of the world, but for all its cosmic expanse, its ostensible concern with immortal gods and other mythical beings, its many and various allegorical implications, it’s also fundamentally human in scope. It can easily be read as the story of a few, interconnected, wildly dysfunctional and toxic families – and what’s more human than membership in a dysfunctional family? And that’s especially true of Die Walküre – everyone on stage, after all, being related by blood or marriage (or even by blood and marriage).

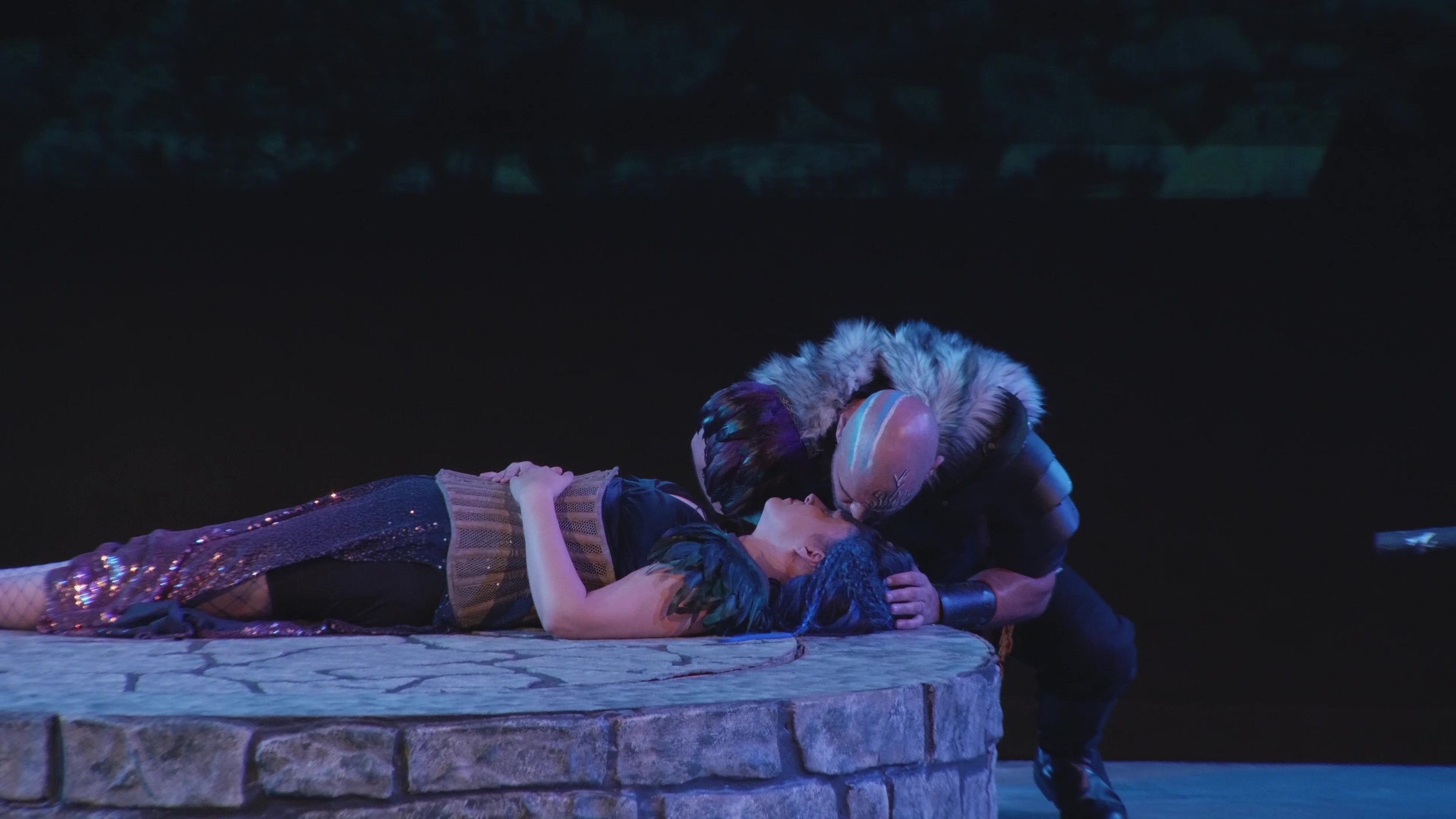

At the center of all the dysfunction, of course, stands the figure of Wotan. I’ve seen very noble Wotans in my time, and very degenerate ones. Regal kings and penny-ante pimps, kindly fathers caught in the awful trap of destiny and incestuous letches deserving of any punishment destiny might mete out. I don’t believe, though, that I’ve ever seen one before so explicitly divided against himself, and broken, and, frankly, so frightfully in need of therapy as Charles D. Martin’s. His Wotan was – believably and movingly – an utter emotional catastrophe. A man (never mind his divinity, he’s a man writ large) of profound feeling, prone to vast and sudden lurches in emotions – from loving tenderness to white hot rage and black despair – but who longs above all else for an almost Buddhist release from feeling and suffering. A peevish and vindictive man, not at all above avenging his own humiliation in losing an argument to his wife (being brought by her literally to his knees) on the person of the loathsome but comparatively powerless Hunding – whom he casually murders with a contemptuously ironic command to go and kneel before Fricka. (And if those two moments are not entirely related I am greatly mistaken.) Yet an undeniably noble man. A man obviously capable of the most extreme cruelty against those he claims to hold most dear, yet – as the music makes clear, and the music never lies – whose love for those dear to him is equally obvious. A man who can go, in something like real time, from joyful, childlike horseplay with his favorite daughter, and heartmelting moments of intimate tenderness with her, to abandoning her to a fate essentially indistinguishable from rape. (A fate to which he had already abandoned another daughter.) And causing the death of another of his children along the way. A man fully prepared to punish his beloved child for doing a thing he desperately wanted done and to part from her forever, yet who takes palpable pride in her growing up and growing beyond him. (It’s no accident that when he finally relents, somewhat, in the severity of his punishment it’s to proclaim that a bridal fire will burn for Brünnhilde such as burned for no other bride before.) Mr. Martin embodied all these wild contradictions. His was a volatile performance, vocally strong (even if he tired somewhat in Act III). And by the time he climbed up on the rock that served as Brünnhilde’s resting place, to cuddle tenderly with her one final time as she slept her enchanted sleep, and to weep silently, it was nearly impossible not to join in that weeping.

Jenna Rae fully inhabited that sleeping goddess, every inch and every decibel the Valkyrie.

From her first appearance, as a high-spirited virginal warrior maiden sparring playfully with her deeply flawed father, to her decision to defy him no matter the cost, to her traumatic break with him and abandonment, and then – an opera later – to her embrace (though not without some profound reservations) of her humanity and sexuality, she does a copious amount of growing up in a very short time (not counting her years unconscious). A psychologically perilous and intense journey. Fully employing the actor’s mysterious “hocus-pocus” Nietzsche so despised, Ms Rae led us spectators through her transformation moment by moment with great insight and lucidity. Her Brünnhilde wasn’t just a mass of notes and some text, but a real person, a girl becoming a woman – under awful and sadly relatable circumstances – before our eyes and ears. And in her playing it was very clear that it was her continual, open-hearted discovery of love in all its forms – filial, romantic, later sexual – in a world where the primal sin was the selfish renunciation of love – that drove her emergence from adolescence into adulthood, from being merely Wotan’s will to being a person, a woman in her own right.

I’ve long held that the last act of Walküre is the best act not only in the Ring but in all of opera, and one of the very best in all of drama of any description; the feelings that it conjures up can be that overpowering. And this TUNDI production did nothing to dissuade me from that – the long Wotan/Brünnhilde scene was as potent as I’ve ever experienced it, thanks to Ms Rae’s and Mr Martin’s wholehearted and generous performances. But I certainly gained a new appreciation for Act II, which in too many productions is a messy barrage of exposition and plot points to be endured between the great, perverse love story that is Act I and the sublime Act III. But in this telling the action was clear: It was all about Brünnhilde arriving at the pivotal – and in Ms Rae’s performance, hugely moving – moment when she makes the dreadful and necessary decision to disobey her father and save Siegmund, becoming the free hero Wotan so longs for but is too blind to see before him.

Wotan and Brünnhilde so dominate Walküre that it’s sometimes all too easy to forget that there are other important characters living out their stories. Happily, these “secondary” roles were filled with terrific singer-actors. Siegmund was sung by Alan Schneider, a truly heroic tenor – his cry of “Wälse! Wälse!” was one of the spine tingling musical highlights of the Festival – one possessed not only of raw power but also a touching lyricism. (He was, unsurprisingly, a magnificent Tristan in 2019.) Katherine Saik DeLugan was a Sieglinde believably the daughter of Wotan; bloodied by fate and her father’s machinations, but unbowed. Together they convinced us not only of the authenticity of their illicit love but also its essential purity. Kirk Eichelberger was a despicable Hunding, though never a cartoonish villain. Sondra Kelly was imperious and implacable in her all too brief scene as Fricka. Even the Valkyries were given a degree of individual psychology. No shrinking violets – they, too, were obviously Wotan’s daughters, doing their best to protect their wayward sister. Waltraute, played by Wendy Silvester, even silently confronted Wotan to his face, trying – though failing – to protect Brünnhilde. The Valkyries, incidentally, were given the great musical moment of the Festival; “shadow” Valkyries in the balconies on each side of the theatre augmented the ones on stage, creating a spectacular, stereophonic effect. It stopped the show. The Festival began well.

I’ll admit I had some slight feelings of trepidation going into Siegfried – which is nothing new for me. While there’s plenty that’s remarkable in it, obviously, and while any of the Ring operas can be underwhelming if badly produced, I’ve found that if one of them’s not going to work, it’s likely going to be Siegfried. And that’s mostly because of Siegfried himself. He does as much growing up as Brünnhilde does in Walküre but while she’s always motivated by love, he’s mostly pushed along by disdain and hatred. And while she’s wise, he’s unenlightened – and that’s being charitable. It’s extraordinarily easy for him to come off as an ignorant and brutal adolescent jerk; not a very attractive character to spend a long night in the theatre with. But, happily, my fears were unfounded – this Siegfried was exceptional, thanks mostly to James Chamberlain in the title role. He gave a powerful, muscular performance, even a heroic one – clearly he was his father’s son. But also a lyrical one. The forging scene was as thrilling as I’ve heard in years, but those few moments of introspection in the forest in Act II were just as affecting. And he still had “gas in the tank” for the long scene at the end with a Brünnhilde who had not been singing for four hours – which is just about the least fair assignment in all opera. Even more impressive, to my mind, he was able to shape the character into something like a sympathetic figure. Instead of stupid and brutal he was innocent and energetic. Naive, yes, and unformed, and with much to learn – about fear and everything else – but basically decent. The best a young person could be and not the worst. For once it didn’t strain credulity, as it often does, that Brünnhilde – after some hesitation – would choose to couple herself to him.

What made Mr Chamberlain’s performance even more impressive was that right before the opera was to begin the conductor, Hugh Keelan, took the stage to announce that he had had COVID and so had had to quarantine for most of the (already brief) rehearsal process, only being able to participate in the last two days. And it was his first time singing the role. As a result, he was still (subtly) on book for large portions of the evening. (He had a score more or less hidden behind part of the set for most of the second act.) Still, he sang splendidly and fully inhabited the character, even when he was forced to be static for stretches of time. Under the circumstances, what would have been “merely” a very memorable performance verged on the miraculous.

Siegfried, of course, is not a one-man show and the rest of the cast was strong. Stanley Wilson was suitably scheming and repulsive as Mime, but also pitiable; a small-time loser with big dreams of the big-time but short on the brains and guts to get there. I was reminded of the characters the great John Cazale played in some of the best films of the 1970s – most famously Fredo Corleone. As the Wanderer, Cailin Marcel Manson was noble and dignified – and defeated. His disguised Wotan had obviously calmed himself since the last time we saw him. Although it could well be the calm of one emotionally cauterized and dead. The calm of one who has decided on suicide but has not yet done the deed. The calm of one who has given up all hope for the world and even the hope for hope, and works only to bring about the End. It was an overwhelmingly sad performance. As was Brian Ember’s as Alberich, though much less noble and dignified. His was an energetically deranged performance – and I mean that as a very warm compliment. He was almost certainly the tallest Nibelung I’ve ever seen, (over six feet, I believe) and so was continually hunched in a variety of striking poses. But of course, Alberich is more emotionally than physically stunted. In Mr Ember’s playing he was the weird incel kid in high school who couldn’t get a date to the prom and now, thirty years later, having made some money, he’s forcing everyone in the world to pay for it. Like Richard III he’s failed to prove a lover so he’s determined to prove a villain. To convince himself that he is a villain. Even if he’s just self aware enough to know that villainy isn’t really all that fulfilling and that he made a terrible mistake stealing that gold. It wasn’t a sympathetic interpretation exactly – just as we don’t sympathize with sexually frustrated men who commit acts of violence – but it was a very human, complex, and fascinating one. Kirk Eichelberger and Sondra Kelly returned as a woozy Fafner and weary Erda, respectively, and Emily Baker was the delightful voice of the Waldvogel.

So, a number of very dramatically effective performances. TUNDI is certainly an actor-centric troupe – to the point that it doesn’t even employ the services of a stage director. Instead – as I understand the company’s process – the actors are much more responsible for building their characters than they would normally be expected to be in more traditional productions. Indeed, in a brief conversation I had with James Chamberlain he explicitly said that what made working with TUNDI special to him was that he was not subject to a director telling him how to feel, but rather he was free to find his own way into Siegfried. In essence, he and the other actors were called upon to be co-creators of the productions. As Roseanne Ackerley, who sang Brangäne in 2019 and Sieglinde in 2022 described it in an interview: “Together, the members of the TUNDI troupe conceive of our character motivations. We also brainstorm staging ideas and our dramatic interactions.”

For practical reasons – it clearly doesn’t have the resources of a major opera house – TUNDI’s rehearsal periods have been extraordinarily short; only a week or two. But it has conducted a number of workshops and practicums between festivals in which the performers have been able to explore the dramas in depth. Some of these have even been open to the public – I was able to attend a workshop in Florence, MA, in early 2023, in which Jenna Rae and Charles Martin, accompanied by Hugh Keelan on piano, worked on the Wotan/Brünnhilde portions of Walküre, followed by the Immolation Scene. The upshot of all this is that the performers have been given space to live with their characters and to work on them – more than they would have been if the operas had been staged more conventionally. I’m reminded of an experiment the theatre director André Gregory conducted in the early 1990s when he gathered a group of actors to workshop Uncle Vanya – which they did for several years, only performing for small, invited audiences, until they documented it on film, calling it Vanya on 42nd Street. The result was characterizations of unparalleled depth and richness. What Gregory achieved with Chekov TUNDI has achieved with Wagner.

This actor-centric philosophy even seems to have extended to the settings. Both of the dramas were played out on simple sets designed by Alan Schneider – a number of hexagonal plinths of various sizes variously arranged to suggest various locales, together with a faux stone platform which served as Hunding’s hearth, Mime’s forge, Brünnhilde’s rock, etc. Scenic imagery (most notably Fafner as a dragon) as well as supertitles were projected onto an upstage scrim, which also served to partially obscure the orchestra which, unusually, performed on stage. Simple but entirely effective and having the great virtue of keeping the focus always on the actors. And of being flexible. TUNDI sure couldn’t afford to build a gigantic Machine, like the Met did, and while they might have missed out on some spectacle that means that they were never really constrained or limited by their set. As I mentioned earlier, this year’s Walküre was essentially an entirely different staging from last year’s. When I asked Ms Rae and Mr Keelan about that they told me that it had arisen naturally, because different actors were playing most of the roles and they brought different ideas about characterization and staging. The simplicity of the sets allowed for that.

Mr Keelan conducted an ensemble of about three dozen players, from reduced scores of his own devising. While the playing wasn’t always note perfect, especially in the brass, I suspect that was, at least in part, a consequence of very compressed rehearsal time. (I’ll also note in passing that at my last full Ring, in Leipzig last year, the great Gewandhausorchester was also far from note perfect; the Ring is challenging for even the most renowned orchestras.) That said, the playing was quite improved over last year’s. And it was notable for its clarity; there were textures and nuances in the music I had never heard, or at least never noticed, before. But most importantly Mr Keelan and his musicians kept things moving. These are long works but they never lagged or seemed slow. Conversely, they were never rushed. (Anyone who was present for Fabio Luisi’s take on the Ring at the Met in the 2010s knows what a really rushed Ring feels like.) Instead, both operas moved along at the pace of drama, as dictated by their own dramatic logic – which is to say they moved along at precisely the right pace. I’ve only heard Mr Keelan conduct five times – and only four separate works – but it’s clear to me that he is a tremendous interpreter of dramatic music.

All in all, some memorable evenings in the theatre. But the Festival experience certainly extended beyond the main stage productions. TUNDI is obviously trying to create a “wall to wall” experience. So they had lectures (this year I attended one about queering Wagner and another entirely devoted to the English horn solo in Tristan) and side concerts (including one where they performed most of Act II of Parsifal – and I wonder if that’s indicative of future aspirations). Brian Ember, whose musical day job is as a rock and roller in the New Haven rock scene gave a concert of his heady and decadent songs. There was even a Valkyrie flash mob outside the local food co-op. But the really notable thing is the feeling of community the Festival has already engendered in just its first three editions.

I’ve been attending Wagner performances for something like twenty-five years now, and I accidentally turned my mother into a Wagnerite something like twenty years ago and ever since we’ve been lucky enough to attend performances all over North America and in Germany. And we’ve made numerous friends and acquaintances – both fellow spectators and even some performers – along the way. Some of my favorite memories of my Wagner adventures involve those friends and acquaintances even more than the shows themselves. Sneaking into MUCH better seats to Parsifal than what we had paid for with a young German composer in Baden-Baden. Having Easter brunch with Brünnhilde in Karlsruhe. Arguing about how best to stage a Ring with a music professor in San Francisco. Meeting and talking to a couple from Quebec in San Francisco and then running into them a year later in Brattleboro. Staying up until the small hours at the hotel bar in Bischofsgrün drinking wine and eating the chef’s special dessert and talking about what we had seen that night at the Festspielhaus with other Bayreuth acolytes – even though we didn’t actually speak a common language. Overhearing some fellow Americans at the Oper Leipzig talking about a Tristan they had heard about in Vermont and, naturally, joining the conversation to describe how wonderful it had been. This, and more, is what being a “Ring Head” has meant to me. And that’s the atmosphere TUNDI has fostered. The morning after the end of the Festival last year my mother and I were having breakfast in a local cafe before getting on the road. We recognized a couple who had been at the performance the night before and casually asked them how they had liked it. And that led to an hour and a half conversation (which could have gone on longer except we all had places to be), and friending on Facebook, and dinner during the first intermission of Siegfried this year and drinks during the second, and plans to meet up again next year. TUNDI’s casts and other creatives have been remarkably accessible and genuinely friendly; it hasn’t been at all uncommon to run into them at cafes or at the food co-op, or even up in the balcony (where we’ve always sat) at the Latchis, when they’re not performing. And since it’s clearly more than just another gig to most of them they’ve had a lot to say about the entire TUNDI project. If a “festival” is a time set apart from the ordinary course of days for special observances and celebrations, then Wagner in Vermont is easily the most festive Wagner I’ve attended in North America and the nearest analogue I’ve experienced to Bayreuth in this country.

Which isn’t to say that TUNDI is a replacement for Bayreuth, or the Met, or the other great opera houses of the world. But at the same time, Bayreuth and the Met, and the other great houses are no replacement for TUNDI. Yes, perhaps TUNDI is a little rough around the edges, just like any mad and improbable (and underfunded) passion project, but it has all the artistic seriousness of those more famous institutions, married to a certain joyous Mickey and Judy gee-whiz-kids-let’s-put-on-a-show-in-a-barn ethos those institutions too often lack. And while I’m looking forward to Rings in Zürich and Berlin next year, and to whatever the Met finally imports to replace the Machine, and while I hope to return to Bayreuth again and again, there’s no question that right now what I look forward to most in the Wagnerian universe is Das Rheingold and Götterdämmerung in Brattleboro in 2024 (they’ve already been announced) and, if all goes well, a full Ring there in 2025. Because, incredible as it may seem, TUNDI, this brave little band of artists in the brave little state of Vermont, is putting on some of the most thrilling Wagner in the world.

C. Tennyson Crowe - October 2023